Oh I'll die I'll die I'll die

My skin is in blazing furore

I do not know what I'll do where I'll go oh I am sick

I'll kick all Arts in the back and go away Shubha

Shubha let me go and live in your cloaked melon

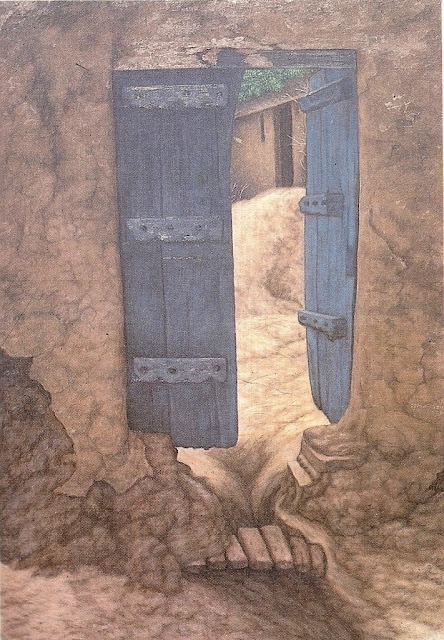

In the unfastened shadow of dark destroyed saffron curtain

The last anchor is leaving me after I got other anchors lifted

I can't resist anymore, a million glasspanes are breaking in my cortex

I know, Shubha, spread out your matrix, give me peace

Each vein is carrying a stream of tears up to the heart

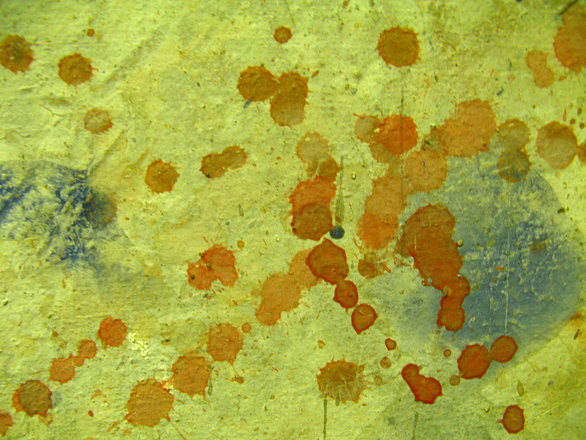

Brains contagious flints are decomposing out of eternal sickness

Mother why didn't you give me birth in the form of a skeleton

I'd have gone two billion light years and kissed God's arse

But nothing pleases me nothing sounds well

I feel nauseated with more than a single kiss

I've forgotten women during copulation and returned to the Muse

In to the sun coloured bladder

I do not know what these happenings are but they are occurring with me

I'll destroy and shatter everything

Draw and elevate Shubha into my hunger

Shubha will have to be given

Oh Malay

Calcutta seems to be a procession of wet and slippery organs today

But I do not know what I'll do now with my own self

My power of recollection is withering away

Let me ascend alone toward death

I haven't had to learn copulation and dying

I haven't had to learn the responsibility of shedding the last drops after urination

Haven't had to learn to go and lie beside Shubha in the darkness

Have not had to learn Usage of French leather while lying on Nandita's bosom

Though I wanted the healthy spirit of Aleya's fresh chinarose matrix

Yet I submitted to the refuge of my brain's cataclysm

I am failing to understand why I still want to live

I am thinking of my debauched Sabarna-Choudhury ancestors

I'll have to do something different and new

Let me sleep for the last time on a bed soft as the skin of Shubha's bosom

I remember now the sharp-edged radiance of the moment I was born

I want to see my own death before passing away

The world had nothing to do with Malay Roychoudhury

Shubha let me sleep for a few moments in your violent silvery uterus

Give me peace, Shubha, let me have peace

Let my sin-driven skeleton be washed anew in your seasonal bloodstream

Let me create myself in your womb with my own sperm

Would I have been like this if I had different parents

Was Malay alias me possible fron an absolutely different sperm

Would I have been Malay in the womb of other women of my father

Would I have made a professional gentleman of me like my dead brother without Shubha

Oh, answer, let somebody answer these

Shubha, ah Shubha

Let me see the earth through your cellophane hymen

Come back on the green mattress again

As the cathode rays are sucked up with warmth of a magnet's brilliance

I remember the letter of the final decision of 1956

The surroundings of your clitoris were being embellished with coon at that time

Fine rib-smashing roots were descending into your bosom

Stupid relationship inflated in the bypass of senseless neglect

Aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaah

I do not know whether I am going to die

Squandering was roaring within heart's exhaustive impatience

I'll disrupt and destroy

I'll split all inti pieces for the sake of arts

There isn't any other way out for poetry except suicide

Shubha

Let me enter into the immemorial incontinence of your labia majora

In to the absurdity of woeless effort

In the golden chlorophyll of the drunken heart

Why wasn't I lost in my mother's urethra

Why was I driven away in my father's urine after his self-coition

Why wasn't I mixed in the ovum-flux or in the phlegm

With her eyes shut supine beneath me

I felt terribly distressed when I saw comfort seize Shubha

Women could be treacherous even after unfolding a helpless appearance

Today it seems there is nothing treacherous as Women and Art

Now my ferocious heart is running towards an impossible death

Vertigo of water are coming up to my neck from the pierced earth

I will die

Oh what are these happenings within me

I am failing to fetch out my hand and my palm

From the dried sperms on my trousers spreading wings

300000 children gliding toward the district of Shubha's bosom

Millions of needles are now running from my blood into Poetry

Now the smuggling of my obstinate leg is trying to plunge

Into the death-killer sex-wig entangled in the hypnotic kingdom of words

In violent mirrors of each wall of the room I am observing

After letting loose a few naked Malay, his unestablished scramblings.