Love, and more

Love after Babel

"Jim Crow segregated hostel

rooms

Ceiling fans bear strange fruit,

Blood on books and blood on papers,

A black body swinging in mute

silence,

Strange fruit hanging from

tridents."

-

Killing the Shambukas, Love After Babel

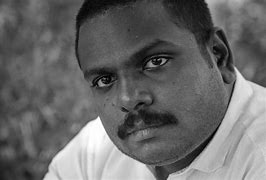

Chandramohan S (CS hereafter)'s third book of poems, Love After Babel, won the prestigious

Nicolas Cristobal Guillen Outstanding Book Award, in January this year. This

review attempts to shed fresh light on CS's work, and analyse CS's highly charged

political treatise as an expression, not only of resistance to Caste-based

oppression, but also that of radical solidarity to other marginalised

identities in contemporary Indian society.

CS identifies himself as a Dalit, Indian poet writing in English. I remember first coming across CS's poetry via his second collection of poems, Letters to Namdeo Dhasal in 2016. (We had briefly corresponded via Social Media, and he was generous enough to have sent me a copy).

One distinctly

remembers the poems of that collection and the fiery emotions they aroused. They

were by turns angry, visceral, and poignant meditations, not only on the nature

and texture of Caste-based historical injustice/violence in a specific context,

but also on injustice of any kind in general. However, CS's main focus in that

collection had been Caste, and Caste-based violence. In this regard, Ajay

Sekhar locates CS's poetry in the Sahodaranist tradition "of subversive

and iconoclastic poetry that aims at social critique and cultural change",

inspired by Sahodaran Ayyappan, a social revolutionary and rationalist who

staunchly advocated democratic ideals in Kerala in the early 20th century. I

would go a step further and say that CS and his oeuvre falls in the greater tradition

of political/protest poetry, championed by the likes of Argentine poet Juan

Gelman, American poet Claudia Rankine and closer home, Meena Kandasamy.

What CS

had started in Letters... only expands

in scale, scope, tone and depth in his latest collection of poems, Love After Babel (2020). By this, I

refer to CS's myriad forays into the geographies of injustice foraged in the

crucible of gender, caste, class, and religion. I also refer to the startling

efficacy of the poems in capturing and articulating the many psychological after-effects

of violence, be they gender-based,

caste-based, religion-based, or identity-based; and how dominant narratives of

identity suppress, coerce, and attempt to obliterate, or worse, re-shape narratives

of 'the other' in their shadow. CS's latest collection is an act of profound

resistance to such cultural hegemony.

The

first section of the collection, 'Call me Ishmail Tonight', with its four very

politically-charged, evocative poems, sets the tone for the rest of the poems.

In 'Thirteen ways of looking at a black burkini' (p3-p4) age-old, patriarchal fear, and the control it

exerts on feminine sexuality and the female body is sharply articulated and

critiqued, when the poet writes, "cops patrol her tan lines/ like dams

patrol/ rivers flowing above danger marks." The female body becomes both, a

site of interrogation and resistance. What are these "danger marks",

who are "the cops", what are these "rivers" that flow above

those danger marks, needs no telling, given that the metaphor is so apt, it expands

in the mind long after one has put down the book. Likewise, Plus-sized poem

(p.47) simultaneously examines and resists prevalent gendered (read: women-related)

notions and expectations when it announces to the reader, "this poem

refuses to be/ the world's wife"

[emphasis mine]. That is because "this poem is not pimple-free/ is printed

on rough paper", neither does it need "introduction from

veterans".

Why loiter? (p.25), inspired by Shilpa Phadke's

seminal book, Why loiter?: Women and risk

on Mumbai Streets, charts how market capitalism has somewhat distorted

prevalent gender dynamics because "the era of open markets/ added colour

to the stale world of white-only lingerie". However, the colour pink (the

deliberate use of a colour with strong gendered connotations to simultaneously

upend such connotations is both brave and noteworthy) spills "over white/

to scrounge for a rump-sized perch/ on the lingerie clothesline." The position

of the poem is clear - while open markets may have distorted gender dynamics,

the struggle to "scrounge for a rump-sized perch" is still on!

But the

interesting thing about CS's gender politics is that his political and

aesthetic preoccupations take in its fold (and attempts to uplift through an

empath's eye for details), not only women, but men and masculinities which find

themselves at the receiving end of various injustices and hegemonies. In the

ironically titled, 'Make in India' (p.34), while the brow sweat of the "lumpen

proletariat" condenses on the bottles of the beverage corporation,

"the frail frame of his wife/ is his daily punching bag". In a matter

of two lines, we feel our sympathies 'for him' ebb away, and suddenly we aren't

sure what to make of the poem. Finally, swallowing the poem with its ironically

positioned title and uncertain morality leaves an acidic taste on our tongues. This

unsettling, acidic aftertaste is the characteristic hallmark of much of CS's

work.

In

the same vein, 'Thirteen ways of looking at a black beard' (p5), illuminates

the uneasy correlation between keeping a beard (presumably by a Muslim man),

and being stopped for frisking "at the immigration office". The poet

tells us, "all you need is in that bag:/ trim your surname,/ make it

palatable for tongues/ at the immigration office". He further elaborates

on the nature of such exchanges by saying, "frisking is not intrusive/ but

very intimate like/ claws gloved with caresses/ patrol the nerve endings of my

civilisation." The penultimate line, "claws gloved with caresses" [emphasis mine] is, one feels, a superbly

evocative image capturing the inexplicable, but very real, prejudice lying at

the heart of Islamophobia in specific, and any kind of prejudicial behaviour in

general, masking itself as pedantic benevolence.

The

range of CS's poetry also manifests in refashioning problematic history to represent,

examine and critique the problematic present. The 'news' in William Carlos

Williams lines, "It is difficult/ to get news from poems/ yet men die

miserably everyday/ for lack/ of what is found there", grimly resonates

with the terrifying image of "a black body swinging in mute silence"

in Killing the shambhuka (p.13) {one of his most famous poems}, reminiscent of

the suicide (or killing) of Dalit student, Rohith Vermula. In a more slanted

way, in addition to protest, resistance and 'writing back to societal hegemony

and oppression', what is found in these poems is empathy, affection and a need

for dignity - the lack of which, at the hands of society governed by

upper-class privilege and prejudice, kills vulnerable men (and women) every day.

Likewise,

the village-legend of Nangeli is resurrected in Nangeli (p.41), about an

"intermediate caste" woman who supposedly cut-off her breasts to

protest against caste-based breast-tax. "The streams [of blood] flowed

unabated"...the streams did not coagulate", the poem tells us,

"the cartographers always miss it".

CS's

poems are some of the strongest poems of protest and resistance one can come

across in the landscape of contemporary Indian poetry. Suraj Yengde, in his

Introduction, aptly posits that at the core of CS's "stoic, rebellious,

confrontational, revolutionary, feminist, humanistic, romantic" poems, sits the notion of "Dalitality", which is,

"an essence of embracing the vulnerability of others".

Indeed,

one is tempted to reflect on the title of the collection itself - Love After Babel . One can read

'Babel' in its colloquial sense, as a mythic enterprise which fails owing to our

inability to effectively speak to, communicate with, and thus understand each

other, thereby giving rise to a sort of universalised 'otherness'.

CS's

poems attempts to map such mythic (but very real) otherness, borne from antagonisms and differences of Caste,

religion and gender. However, it is unique in that it fashions an original

aesthetic founded in the mould of startling imagery fused with an

understanding, empathy and courage to reach out and touch the other, not through "gloved claws", but through love.

That CS invents a completely original poetic idiom in doing so, simultaneously enriches

and deepens the scope his project.

As an

endnote, Eduardo Galeano had once written of Juan Gelman, that "Juan has

committed the crime of marrying justice to beauty".

I'd hazard and say, so has CS!

■■

Author : Chandramohan

S

Book : Love

After Babel

Publisher : Daraja

Press, Ottawa, Canada

Year : 2020

ISBN-13 : 978-1988832371

Pages : 90

pages

Price : INR 695.00

(Ankush is a mental health professional and poet based in Delhi. His first collection of poetry, An Essence of Eternity (Sahitya Akademi, New Delhi) was published in 2016. His poetry has appeared in Indian Literature, Eclectica, Cha: An Asian Literary Journal and Linden Avenue Literary Journal. He is currently pursuing his PhD in Masculinity Studies from BITS, Pilani. )

No comments:

Post a Comment