We present to you the first part of the excerpt (reprint) from Finding Neema by Juliet Reynolds ( Hachette India, 2013)

|

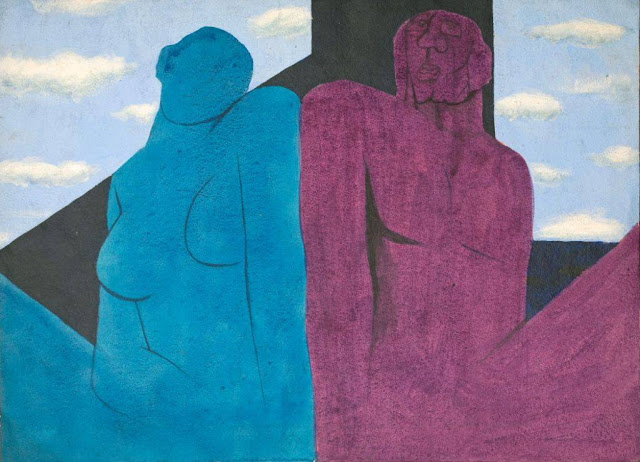

A painting by Hungryalist painter Anil Karanjai

Source: Facebook page (with permission from his wife Juliet Reynolds)

|

Anil and I were from very diverse backgrounds, an assertion I make without allusion to our ethnic origins. It was the social milieu we grew up in that most defined our distinctions and made our marriage a rare one. But it was Anil more than me who touched us with an uncommon brush: almost invariably in alliances like ours, the Indian husbands of European memsahibs are the product of the English- educated, westernized classes and with Anil this was demonstrably not the case. Socially and economically of the lower middle class, the medium of his schooling was his mother tongue, Bengali and, until his early twenties, by which time he was already a professional artist, he barely spoke English. From early on in our relationship, I realized he was all the better for this, as he had much deeper roots in his own culture than other Indian men I had chanced to encounter. Yet, at the same time, he was thoroughly cosmopolitan and progressive in outlook.

The most crucial years of Anil’s intellectual formation were the 1960’s when his hometown, Benaras became a hub of radical politico-cultural activity of both a national and international character. At the very beginning of that unparalleled decade, he had joined ‘Hungry Generation’, an avant-garde group of writers and artists, active largely in Calcutta. Subversive to the core yet supremely creative, the ‘Hungryalists’ had shaken up the establishment to such a degree that some had lost their jobs and were briefly jailed. Covered in a special story by Time Magazine, the group had been closely connected with the Beat movement and had influenced Allen Ginsberg during his sojourn in India. As one of the few visual artists active in the movement, Anil had illustrated their publications and designed their posters. Although he was at odds with the nihilism and anarchy of ’Hungryalist’ ideology, he felt blessed to have been part of a movement that made so vast an impact on modern Indian culture. It was an experience that would mark him for the rest of his life.

In the final years of the sixties, after the ‘Hungryalists’ had gone their separate ways, Anil continued to engage in anti-establishment activities and to create in a cosmopolitan environment. A frequent visitor to Calcutta, a city then fired by the spirit of revolution, he sought out senior artists who could guide his hand and help strengthen his artistic vision. Back home in Benaras, he and other artists ran a collective studio they called the ‘Devil’s Workshop’, and they converted a rundown teashop into the city’s first gallery. For a while they also lived in a commune, a place of intense exchange between idealistic young people from many countries. This was a time when Anil and some of his friends experimented widely with consciousness expanding substances, including LSD and, of course, derivatives of cannabis, then an accepted facet of Indian culture; this was especially so in Benaras, the city of Lord Shiva, where these substances formed an important part of religious practice. But Anil never over-indulged or experimented irresponsibly. Ideologically committed to the far left and determined to become an accomplished artist, he was always passionate and serious-minded. There was no room in his life for self-indulgence, fickleness or frivolity.

It was many years into our relationship before I came to understand that Anil was never as fulfilled as he had been in the sixties. The immense collective energy he’d experienced during that decade was never to be reignited, and he felt the loss intensely. And because I was never able to compensate for that loss, I have an abiding regret that I missed out on that experience.

I was nine years Anil’s junior and at the time he and his comrades were agents of change in the world around them, I was still a schoolgirl in knee-high brown socks, incarcerated with nuns at a boarding school in south-west England. My mother was an Irish catholic and at the time of her marriage to my English protestant father, she had solemnly vowed that all their issue would be brought up in the faith of the Roman Church. As one who grew up to denounce all forms of doctrine and institutionalized belief, I never quite forgave her for making such a promise on my behalf. Even as a young child, I was blasé about rituals and catechism classes, I found Sunday Mass a torture and I thoroughly disliked most priests and nuns. At first, my mother took this in her stride, thinking I would grow out of it. Sometimes she was even amused by my heretical leanings. She never forgot an incident when, during a Sunday sermon, I complained about the priest who was exhorting his parishioners to donate money to the church fund instead of propagating the message of Christ; though I was only about six, my complaint was audible to the entire congregation as well as the priest; from that time, I was looked at askance by the Reverend father.

But if my mother believed that my non-conformism was just a phase, she would be in for a rude shock as I entered my rebellious teenage years. Like most of her generation, she was entirely unprepared for the advent of the sixties and of the electrifying effects of this era. The voices of the sixties’ anti-establishment culture were heard by my generation irrespective of class and made us feel liberated and euphoric. But because they so manifestly contradicted whatever we’d been taught, they also made us confused and angry. All teenagers experience conflicting emotions, sometimes very violently, but I believe that in the sixties the contradictions we grappled with were especially fierce. I found It impossible to reconcile worshipping John Lennon and loving the Rolling Stones, having been conditioned by a religion that promised eternal hell and damnation for merely skipping Sunday mass, or commanded one to recite a string of Hail Mary’s for thinking ‘lewdly’ about boys.

~*~

Anil, too, was a religious dissenter. A Brahmin by birth, he’d already begun to argue with the pundits of Benaras before entering his teens; he’d then studied in depth the Hindu sacred texts like the Ramayana and the Bhagavad Gita so that he could take them on, exposing the gaps in their knowledge and the contradictions between the dharma they preached and their actions. Abjuring the caste system, Anil deliberately spent time with people and in places considered inferior or unclear by the Brahmin orthodoxy. Eating beef in the city’s Muslim quarter was one expression of such dissent, and he would grow up to feel protective towards this quarter’s poor inhabitants, mainly weavers and their families, who were vulnerable to attack by Hindu mobs. Once he single-handedly confronted such an entity, challenging its adherents to kill him before proceeding to perpetrate whatever acts of brutality they had in mind; since killing a Brahmin is one of the most grievous sins a Hindu can commit, the mob dispersed in fast and cowardly fashion. Around that time, one of his younger brothers had come under the influence of right wing Hindu ideologues; the differences between the siblings often led to fierce arguments, creating an atmosphere of tension in the home.

The Karanjai family were refugees from East Bengal, casualties of Partition in 1947. Anil was a small boy when this great upheaval took place, but he had witnessed no bloodshed or communal hatred; he recalled that their Muslim neighbours had been reluctant to see them go and that tears had been shed by people from both communities. Anil’s father had taken the wise decision to eschew Calcutta, where middle class refugees would find themselves facing appalling circumstances, many forced to live in slums; in Benaras, the family’s living conditions would be much more tolerable, humble but not humiliating. Anil’s father practiced homoeopathy, treating the poor for routine complaints; he also tried his hand at running small businesses, but was unsuccessful, so that his six children grew up facing considerable hardship. Anil responded to this situation by becoming independent as early as he could. He never fought with his parents, but from the age of about fifteen he spent most of his time away from home. Having already begun to practice art, he dropped out of school to join his master’s institution where he soon excelled to such an extent that he became a teacher to his fellow students.

Anil’s independent spirit and his parents’ acceptance thereof ensured that I would encounter none of the difficulties faced by young western memsahibs embarking on marriages with Indian sons, above all Brahmin ones. I had little interaction with the Karanjai family but on the few occasions I visited their modest home in Benaras, they treated me with kindness, warmth and respect. That I attempted to communicate with them in Hindi and with the smattering of Bengali I had picked up from Anil helped a good deal, as they seemed to find this both touching and funny. They had long since given up the idea that Anil would live an ordinary middle-class life, and they accepted our marriage without demur, as though it were an expected and natural occurrence. When we married formally, none of Anil’s family or mine was present. As we had lived together for several years and already thought of ourselves as husband and wife, we were wed privately with only a handful of friends present to act as witnesses. I was very grateful to Anil’s family, as also to my mother, for their progressiveness in the face of so unorthodox a union.

~*~

In India, even when visiting the most awe-inspiring monuments, I had never once felt overpowered. Rather, my experiences of Indian art had almost invariably offered me a feeling of wholeness and belonging, of a rootedness in the earth. It would be inaccurate to state that my love affair with India began and ended with art, but it is mainly because of art that I remained here and found a direction for my life. My marriage to Anil had not initially been in the reckoning, for I confess that until we met in the late seventies, I had been unconcerned with contemporary Indian art. I shared the prejudice of most Europeans that the country’s artistic achievements belonged firmly to the past. I had seen and appreciated some of the early 20th century masters of Bengal, but I had written of what I had seen of contemporary artists’ work as derivative and boring.

Anil was to change that view even before we had met; in fact the changed perception he wrought in me was the very instrument of our meeting. Put simply I fell in love with his paintings before falling for him. I had seen a few of them at the home of a friend, a contemporary of Anil’s from Benaras, and I was immediately drawn to the imagery: faces and limbs emerged forcefully from natural forms like clouds, rocks or trees or from man-made forms, mainly ruins. These strange humanized landscapes reminded me of nothing I had seen before and I found them very refreshing and challenging. I was also impressed by Anil’s technical competence and by the breadth of his vision; though his images spoke of suffering and oppression, there was a great positivity, a sense of overcoming, sometimes conveyed with a touch of sardonic humour and occasionally with glimpses of a soft romanticism.

My obsessive desire to meet the artist was maddeningly thwarted by his absence in the USA. In an attempt to overcome this mighty obstacle, I wrote to him offering to organize a retrospective exhibition of his work at the Jehangir, a well-known public gallery in Bombay. My offer was promptly accepted; Anil said that away from India he had felt uprooted and creatively uninspired, and I had provided him with a good reason to return.

Anil and I first came face to face in the early days of 1978, about two months before the scheduled retrospective. After some hesitant moments, unsure of my responses, I knew I was passionately attracted to him. He was a good bit shorter than me but his magnificent mane of Afro hair made him stand tall and was most appealing. As to his face, he had a beautifully shaped, generous mouth, neither too full nor too narrow. But it was his eyes above all that reflected his charisma; huge, luminous and intense, above high, chiseled cheekbones, these spoke of a character that was fiery and dreamy at the same time.

We became a couple almost immediately, a development that gave rise in me to powerful but conflicting thoughts and emotions. On the one hand, our being together seemed not only very natural but also as if we’d been together for eons; sometimes in Anil’s presence I was overcome by a sense of déjà vu, a feeling I rather enjoyed and even desired. On the other hand, I had tremendous difficulty adjusting to my new relationship with a man as commanding as he was. For the first time in my life, I found myself dominated much of the time and this often led to explosions. We decided to defer any decision about our future until after the exhibition, the preparations for which were hectic.

When at last we reached Bombay and the paintings were mounted, the retrospective took place with considerable fanfare and a good measure of success; it was attended by a wide public and received excellent press coverage; a few paintings were sold to appreciative collectors and the exhibition was extended for three weeks at the Chemould, a respectable commercial gallery located above the Jehangir. During those weeks, Anil and I spent some deliriously happy, carefree days in Goa, By the time we returned to Bombay we had resolved to try out a life together. Within a couple of months we settled into our first barsati in Delhi …

No comments:

Post a Comment