We present to you the second part of the excerpt (reprint) from Finding Neema by Juliet Reynolds ( Hachette India, 2013)

When I first entered the Indian contemporary art world in the late nineteen seventies, the atmosphere was much healthier and more motivating than today’s. The art market barely existed and there was more communication and camaraderie between artists. This is not to say that groups or cliques did not then exist. Art politics frequently reared its head, tending to be petty in nature, with artists fighting over the crumbs thrown from the table of the private or corporate collector or from state run institutions like the Lalit Kala Akademi; only once in a while were serious issues raised and the battle lines drawn on ideological grounds. But despite all the wrangling, the environment was quite relaxed and welcoming. I thoroughly enjoyed being a part of this environment and becoming familiar with the artists and their work. Almost every afternoon or early evening, Anil and I would view exhibitions and then meet our friends in the garden canteen at Triveni Kala Sangam, the multi-arts institute close to Connaught Place, New Delhi’s hub.

Connaught Place was also the scene of the Saturday Art fair, a weekly event marking a strong anti-elitist movement. Anil was one of the best known artists to participate in this regularly, but the leader was his senior, Suraj Ghai, a close friend and, like him, the archetypal anti-establishment artist. Apart from exhibiting their artworks in the park, the participating artists also painted or sketched on the spot with people and landscapes as their subject. I found myself drawn into this activity, in the beginning reluctantly because of my poor skills, but I soon began to enjoy myself; I became quite uninhibited which surprised me a god deal as we often attracted large crowds around us.

Beyond my modest artistic strivings, I learned a lot from the Saturday Art Fair experience. Our interaction with intellectuals and activists from other fields – poets and writers, film-makers, journalists and leftist theatre troupes – was both lively and enlightening. Sometimes there were fierce arguments about ideology and creativity or about how to take on the art establishment. Sadly, the movement fizzled out within two or three years because the logistics of organizing it were too demanding on the artists, many of whom had fulltime jobs. Moreover, the municipal authorities and the police were against it; on several occasions they swooped down on the exhibits and attempted to seize them. Everyone decided to move on to less irksome activities.

~*~

The art world began to change in the latter part of the eighties, and although the change at first was slow and insidious, it would soon become rapid and sweeping. Following the assassination of Indira Gandhi in late 1984, the first steps were taken towards opening up the Indian economy, and these were paralleled in art by the invitations extended to Christie’s, Sotheby’s and other international auction houses to hold sales of Indian contemporary art in this country. Sotheby’s also attempted to establish a permanent foothold here in order to gain legitimate access to India’s heritage. Although the attempt was foiled, the notion of an Indian art market took root through the periodic sales held under the auspices of these auction houses, and a new class of art patrons thus emerged. The ones to benefit from this development were the already established artists and some of the lesser known artists belonging to the cliques they controlled. Almost overnight, the prices attained for the works of such artists increased manifold, jacked up by artificial means. A true art market is never created suddenly by discriminatory measures. It grows over time within a regulated structure, encouraged by tax and other fiscal incentives. But in an economy such as India’s, which thrives on black money, no-one had interest in changing the status quo to benefit art.

In the midst of the sham commercialization of Indian contemporary art, I was increasingly turning my attentions away from teaching towards my writing. I was a teacher neither by training nor temperament, but during the near ten years I was engaged in education, I’d enjoyed the experience and had learned a great deal. In order to teach my mother tongue to young foreigners, I’d been obliged to study in depth its grammar so that I could explain its rules and idiosyncrasies in a thorough, logical manner. Expressions, structures and usages I had taken for granted had now become a matter of inquiry and I found this gratifying. I was also rewarded by finally finding use for my years spent studying speech and drama. For one thing, I discovered that teaching the basics of English phonetics helped learners overcome their difficulties in pronouncing the language, and I tried to achieve this in an entertaining way by adopting a somewhat theatrical style when articulating sounds and making them repeat these. I further discovered that drama was a wonderful tool for teaching a foreign language. Through the enactment of sketches, scenes and short plays, some of which I myself wrote, my students picked up spoken English much more rapidly than they did in their language classes.

Despite the satisfaction I derived from teaching my only regret in giving it up was economic. The good experiences it had afforded me did not repeat themselves; rather, as time progressed, I was increasingly landed with spoilt, unmanageable teenagers who made racist remarks about Indians and had little interest in learning. But having a regular income, and a fairly good one at that, had alleviated the stress Anil and I had faced when we began to share our lives.

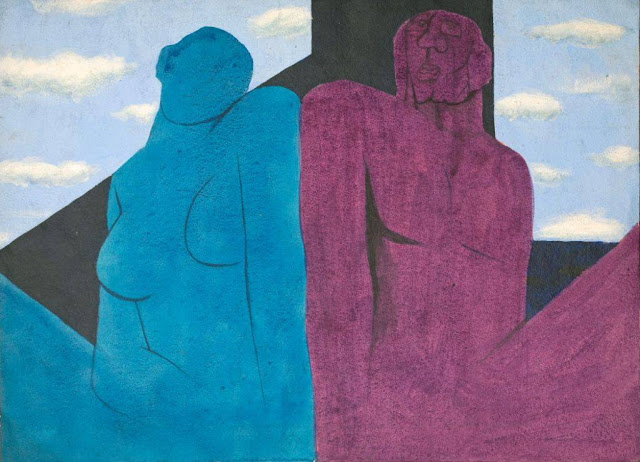

The strain of those days had been almost entirely financial. Our relationship was fiery, and we sometime fought fiercely, but we were in the main very happy. Our economic struggle was a mundane matter calling for practical solutions, not diminishing our enjoyment of life. For our first two years we slept on a mattress on the floor and had no fridge, but these discomforts barely bothered me. Paying our rent and bills when we were down and out did cause problems and, Anil was sometimes obliged to sell his paintings at abysmal prices, always a miserable solution for an artist.